Syringe-based fillers and autologous fat transfer to rejuvenate the periorbital region

Volume loss has increasingly been recognized as an important aspect of facial aging. This is especially true of the periocular region. Restoration of this lost volume can be achieved through placement of syringe-based fillers, autologous fat, or implants. This article discusses the use of syringe-based fillers (hyaluronic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite) and autologous fat transfer to rejuvenate the periorbital region. The periorbital complex consists of the brow, superior orbital rim, upper eyelid, lateral canthus, lower eyelid, inferior orbital rim, and upper cheek. The most important of these in the aging process of volume loss is the interface between the lower eyelid and upper cheek or midface. Systematic aging begins throughout the periorbital complex beginning in the patients mid-to-late 30s.1 The extent and rapidity of periorbital aging varies between individuals and is strongly dependent on the relationships between the bony orbit, globe, and malar complex. The periorbital are ages at a faster pace and earlier in life with a negative vector midface, much as the jaw line and neck age earlier in people with microgenia and a short thyromental distance (Fig. 1). Some individuals even display lower eyelid bags in youth; these bags appear early because of the negative vector produced by the deficient anterior projection of the inferior orbital rim in relation to the globe.

YOUTH

The youthful upper periorbital complex consists of a brow that is full over its entire height, being propped up by the volume of the brow fat pad. Entire articles have been written and rewritten about the normal aesthetic height of the brow.2 The authors are well aware of these aesthetic norms but maintain that patients differ tremendously regarding their natural brow height. They ask their patients routinely about their brow position in youth and strive to restore this relationship, only changing natural brow position after careful consideration. Comparing photos in the latest fashion magazine shows many examples of models, all of whom are exquisitely attractive, with significantly differing relationships between the brow and superior orbital rim (Fig. 2). The upper eyelid also shows a variable fullness between patients; all may be considered youthful and attractive. Some individuals have significant tarsal show with a deep superior orbital sulcus, a high lid crease, and very little dermatochalasis. Others have very little tarsal show with a more prominent orbital fat component and therefore, a much fuller-appearing upper eyelid and a tendency toward greater dermatochalasis. In the authors opinion, the restoration of the youthful upper eyelid and brow complex must be tailored to each patients unique characteristics and must strive toward the restoration of youthfulness and not an ideal appearance based on the biases of the surgeon.

Some rejuvenation of the upper eyelid complex relies on surgical lifting procedures that are beyond the scope of this article. However, restoration of the upper periorbital volume is addressed. The youthful lower eyelid complex revolves around the appearance of a short lower eyelid, or rather, a superiorly placed and full upper cheek. The lower eyelid cheek interface should be at the lower tarsal border and flow into a full convex upper anterior cheek. This natural convex fullness results from the quantity of the lower eyelid suborbicularis oculi fat or SOOF and also depends heavily on inferior orbital rim projection (Fig. 3). The youthful lower eyelid must also lack pseudoherniation of orbital fat. The cheek skin should be smooth over the underlying fat and the malar cheek fat pad should be shaped as a teardrop, with the rounded leading edge of the tear inferior-medial and tapering laterally over the anterior aspect of the zygomatic arch. The inferior aspect of this teardrop should create a subtle shadow in its interface with the buccal region that parallels that of the jaw line (Fig. 4). These features lead to the overall appearance of the heart-shaped face of youth.

Fig. 3. Youthful lower eyelid complex with short-appearing lower eyelid and smooth transition between the lower eyelid and cheek compared with typical aged lower eyelid cheek complex with a long-appearing lower eyelid and orbital groove.

AGING

Aging is the culmination of a multifactorial process that includes the actions of gravity, volume loss, and skin changes due to intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Volume loss in the periorbital area leads to exposure of harsh bony contours and the creation of shadows indicating aging. In the superior rim, this also leads to an apparent descent of the brow. As volume is lost over the bony orbital rim, the support for the soft tissue brow is lost. This effectively raises the position of the bony rim, which is now harsh and skeletonized, and leads to an apparent drop in brow height because the hair-bearing eyebrow now rests in a lower position relative to the superior orbital rim. This volumetric contribution to brow aging is not the only component. Forehead, brow, and upper eyelid aging is a complex process with a gravitational contribution that may benefit from surgical lifting procedures; however, volume is an important consideration. Photos of the patient when young are a valuable tool in assessing the relative contributions of different factors in periorbital aging, thus assisting the surgeon in the appropriate selection of rejuvenation techniques. Lower periorbital/cheek aging is most significantly influenced by volume-related changes. With time, the heart-shaped youthful face gives way to the more rectangular face of age. Some of this is due to the development of jowling and lower facial aging, which is beyond the scope of this discussion. The loss of volume in the lower eyelid/cheek complex, however, is a key contributor to the rectangular face. Additionally, volume loss allows the appearance of shadows, as tissues fall and become tethered by various retaining ligaments. Double contours arise in the lower eyelid and cheek, with exposed orbital fat creating a bulge, the exposed bony orbital rim creating a hollow, malar mound bulge, and malar septum hollow (Fig. 5). The lower eyelid gains apparent length in this process. Pseudoherniation of lower eyelid orbital fat combined with loss of orbital rim volume leads to lengthening of the lower lid height and inferior placement of the lower eyelid cheek junction. This is the orbital groove/tear trough deformity. Below this, the malar mound and malar septum create a second double contour in the cheek region. Restoration of youth combines removal of orbital fat pseudoherniation, if indicated, and placement of volume into the orbital groove/tear trough and cheek region to restore the single convexity of the cheek and raise the cheek eyelid junction, thereby shortening the apparent lower lid height.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

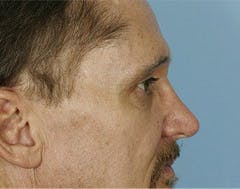

Although people are becoming more educated about volume loss as a cause of their facial aging, patients rarely present for consultation requesting a fat transfer. Patients express concern that they appear tired or that they have persistent dark circles under their eyes. A detailed assessment is necessary to determine the cause of their concerns and what part of this is due to volume loss. Review of patient photographs from their youth is helpful, but if these are not available, pointed questions about eyelid appearance and brow height can help differentiate between agerelated changes and normal anatomic variation. A detailed history and physical examination is indicated; however, the authors limit discussion to the key factors related to volume replacement. Much of forehead and upper eyelid rejuvenation relies on incisional techniques. However, brow position and brow fat quantity should be assessed. In many instances, the brow height is adequate, and adding volume alone to the superior orbital rim will restore a youthful appearance. A hollow superior orbital sulcus may also be restored with volume, although this is an advanced technique and careful patient consultation should take place regarding the likelihood of contour irregularities. The authors address the hollow superior orbital sulcus with a patient only if it is a specific concern and usually offer intervention only if it is due to previous surgical misadventures and not a natural occurrence. The mainstay of patient assessment for volume replacement involves the lower eyelid and cheek. Assessment of the lower eyelid and cheek begins with determining if orbital fat pseudoherniation requires addressing. This determination is made by evaluating the patient in oblique and lateral views. If the orbital fat protrudes anterior, beyond the surgeons perception of a natural convex cheek eyelid interface, a blepharoplasty should be considered (Fig. 6). This usually involves only the medial and middle fat compartments because the lateral fat compartment less commonly protrudes beyond the desired convex line.

Fig. 6. Comparison of lateral views of patient on left who lacks steatoblepharon and underwent only a fat transfer and patient on right with a sufficient steatoblepharon to warrant a transconjunctival blepharoplasty and fat transfer.

A transconjunctival technique is used with minimal exposure because the tissue planes need to be preserved over the orbital rim for concurrent fat grafting. An assessment of overall midface volume and position is also performed, noting a negative vector midface (prominent eyes), the presence of a malar groove, malar septum, and malar mound, especially if early festooning is present. Assessment of the lower cheek is also made, including buccal hollowing and perioral volume loss. Once assessments of the relative contributions of volume loss have been made, a conversation with the patient may begin regarding intervention. Patients presenting earlier in the aging process who lack significant volume loss or a bony negative vector and who do not require a lower eyelid blepharoplasty are candidates for office-based volume replacement with syringe-based fillers or surgical treatment with autologous fat. As patients develop more severe volume loss that would require multiple syringes of filling material to achieve results, the financial outlay on the material makes fat grafting a better option. Additionally, fat has the advantages of being durable with longterm graft survival. Each option, including its longevity, down-time, results, and cost, are discussed with patients, following which they can select the procedure that best fits their wishes.

HYALURONIC ACID TECHNIQUE

Hyaluronic acid (HA; Restylane, Restylane Lyft, Juvéderm, etc) is used for patients who do not have a severe degree of aging or who have a greater degree of aging but wish to avoid the expense or recovery associated with more invasive procedures. 38 The HA is mixed with 0.2 mL of 2% Xylocaine with 1:100,000 units of epinephrine using a sterile stainless steel double Luer-Lok coupling. For the brow, no other anesthesia is used. For the lower eyelid and cheek, a small amount of 1% Xylocaine without epinephrine is place through an intraoral route at the infraorbital nerve foramen. Brow injection is performed by palpating the reflection of the supraorbital rim with the index finger and thumb of the nondominant hand. A direct injection deep to the orbicularis muscle and superficial to the periosteum is performed in small aliquots until brow fullness is restored. Care is taken to avoid the supraorbital neurovascular bundle. Injection is usually lateral to this landmark. For the lower eyelid orbital groove/tear trough, the area to be injected is first marked out with a fine-tip surgical marking pen. The premixed HA is then injected with a 31-gauge needle beginning medially. Care is taken at the medial injection point to avoid the angular vein, and aspiration is performed before injection. The material is placed just superficial to the periosteum in small aliquots. Injection then progresses laterally, placing more material adjacent to the last injection until a confluence of the smaller injections occurs. Gentle massage can be performed to manipulate the material into a smooth configuration (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Patient undergoing HA injection into the orbital groove. The area for injection has been marked out. The photo on the left demonstrates the medial groove being injected and on the right, nearing completion of the right lower eyelid.

Once the initial deep injection is complete, further material is added just deep to or within the orbicularis muscle to further refine the area. On the second pass, the area is anesthetized from the local anesthetic placed during the first pass. This allows further refinement to be precisely performed with no patient discomfort. Observation is made of the superficial veins of the lower lid, which are avoided. If any bleeding occurs, pressure with a Q-tip or gauze is immediately performed to minimize bruising and prevent an accumulation of blood, which makes assessment of correction difficult. The goal is to achieve barely full to slight undercorrection. The authors err on the side of undercorrection; a ridge of filler may be visible with any degree of overcorrection (Fig. 8). Lower eyelid filler always creates small pinpoint areas of ecchymosis, which usually resolve within 3 to 5 days and can be easily covered with makeup. More significant bruising occasionally occurs but can usually be avoided by having the patient eliminate any blood-thinning medication in advance. The most common complication is undercorrection, which may be touched up 2 to 4 weeks after the initial treatment. Patients are told that a small touch-up may be required to achieve optimal results. Most patients are satisfied with one treatment and most do not seek refinement. Small contour irregularities can usually be manipulated with gentle massage and will resolve. More significant overcorrection should be avoided, but in the most severe cases, hyaluronidase may be used in small quantities to enzymatically degrade the product. However, this usually leads to near-complete return to the pretreatment appearance.

Fig. 8. Oblique photos of a patient demonstrating an isolated orbital groove before and after treatment with HA filler. After photo is 3 months postprocedure.

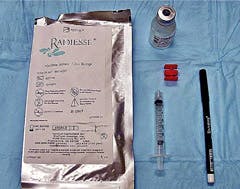

CALCIUM HYDROXYLAPATITE TECHNIQUE;

Radiesse (Bioform Medical Inc, Franksville, WI, USA) is a synthetic injectable implant composed of smooth calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA) microspheres (diameter of 2545 mm) suspended in a sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel carrier. Radiesse is Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the correction of moderateto- severe facial folds and wrinkles, such as nasolabial folds, and for the correction of signs of facial lipoatrophy in HIV-positive patients. There are also FDA clearances for oral/maxillofacial defects, vocal fold augmentation, and radiographic tissue marking. Radiesse does not contain any animal products, and skin testing is not required before use. Upon injection, it initially acts as a filler. It is easily malleable, can be used to shape and contour large areas of the face, and provides results patients can appreciate immediately. Once injected, the CaHA microspheres are slowly

degraded by the body and stimulate neocollagenesis. Most authors report a treatment effect that lasts 6 to 12 months (Fig. 9).9,10 For treatment, the patient is placed upright in a chair so that the ptotic malar fat pad can be easily seen.

The ideal shape and position of a youthful-appearing malar region is then marked directly on the patients skin (Fig. 10). This triangular-shaped area may be treated with a topical lidocaine cream and then injected with a small amount of 1% Xylocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. Additionally, an infraorbital nerve block is performed by passing a 27-gauge needle into the canine fossa via the gingivobuccal sulcus and injecting a small volume of 1% Xylocaine. Although allowing for adequate anesthesia and vasoconstriction, the Radiesse is prepared by adding 0.2 mL of 2% Xylocaine with 1:100,000 units epinephrine to the 1.3-mL Radiesse syringe and vigorously mixed. The addition of the lidocaine decreases the viscosity of the filler to allow for greater malleability and provides additional analgesia for molding across the inferior orbital rim. A single injection site in the middle of the area to be filled is selected. The needle is introduced adjacent to supraperiosteal tissues and the Radiesse mixture is slowly injected to create a depot of material that can then be molded into the desired shape. This technique is in contrast to the serial puncture or linear threading techniques commonly used in delivering fillers. Alternatively, the Radiesse can be injected transorally after an infraorbital nerve block and localization of the canine fossa(Figs. 11, 12). Care is taken not to inject too superficially within the dermis of the thin lower eyelid skin or too deeply into the postseptal orbital tissue. The authors do not advocate using Radiesse to treat the tear trough. Immediately following the procedure, the patient should apply ice and pressure to prevent bruising. The significant advantage of the Xylocaine dilution is the ability to mold or sweep the product across the inferior orbital rim. An advanced technique would include a more limited depot medial to the infraorbital nerve foramen onto maxillary periosteum with gentle sweeping of product upward. There should be great caution to avoid delivery of product proximal to the foramen because parasthesias have been a reported complication of injection adjacent to sensory nerves.

Fig. 11. Transcutaneous and transoral depot injection of Radiesse.

AUTOLOGOUS FAT TRANSFER TECHNIQUE

Autologous fat transfer is performed in the operating room under intravenous sedation supplemented with local anesthesia. Skin resurfacing and lower eyelid blepharoplasty are performed before fat transfer, if indicated. If an endoscopic brow-lift is planned, fat transfer is performed in all areas except the brow before the brow-lift and fat is placed in the forehead/brow region following the incisional lift. Any patient markings are performed in the holding area with the patient upright. The only recipient marks made are of the prejowl sulcus because the other areas are easily assessable with the patient supine while using preoperative photos. Donor areas are marked out in the holding area with the patient standing. The abdomen is the first choice of donor area, if available, followed by the medial and lateral thigh (Fig. 13).1114 Once in the operating room and under sedation, the donor areas are infiltrated with 1% Xylocaine with 1:100,000 units of epinephrine mixed 1:1 with injectable 0.9% saline. The injection is performed with a 20-mL syringe and a 3-in by 25-gauge spinal needle. For the abdominal area, approximately 30 to 40 mL of solution is injected.

Injection is placed in the immediate subcutaneous space and the prefascia space. No injection is placed in the midcutaneous plane where the fat is to be harvested to minimize possible toxicity to adipocytes from the Xylocaine. Usually, between 60 and 100 mL of fat is harvested. The leaner the patient, the less oil contained in the harvested fat. For heavier patients, the fat contains a higher degree of waste and larger quantities may be harvested. Harvesting is performed with a small 15-blade stab-type entry point placed appropriately for the donor site. A bullet-tip 3-mm by 15-cm cannula (Tulip Medical Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) is used for harvesting with a 10-mL syringe. Gentle (2 3 cm) aspiration pressure is used to prevent lipolysis. The nondominant hand is used to stabilize the fat pad, while the dominant hand places the cannula in the midcutaneous plane. However, the fat should not be pinched up to prevent nonuniform harvesting and resultant contour irregularities. Before repositioning the cannula, 3 to 4 passes are made in one tract. When repositioning, the cannula must be brought nearly out of the incision to prevent the illusion of harvesting from a new area when the same local area is being used. This limits the amount of fat harvested and may lead to contour irregularities. One must be mindful of the cannula tip location at all times. Once completed, the entry incision is closed with a single subcuticular 5-0 monofilament polyglyconate suture. The 10-mL syringes of fat are capped with a stainless steel plug intended for fat transfer, the plunger is removed, and the syringes placed in sterile sleeves in the centrifuge. The fat is spun at 3000 rpm for 2 to 3 minutes. The supernatant, which contains free fatty acid from lysed cells, is poured off into gauze. This should be performed before removing the plug to avoid loss of suction and the fat tumbling out. The plug is removed, the syringe placed in a sterile test tube rack, and the infranatant of blood and anesthetic solution is allowed to drain onto gauze (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14. The supernatant oil is drained off while the syringe is capped. The cap is then removed and the blood and fluid is drained from the infranatant.

The 10-mL syringes containing the purified fat are combined into a 60-mL syringe, and the air is removed by gentle stirring. Depending on the patient, approximately 50% to 75% of the harvested volume is injectable fat. The fat is transferred via a Luer- Lok transfer hub to 1-mL injection syringes. Three different injection cannulas are used for all injections: 1.2 mm by 6 cm and 0.9 mm by 4 cm spoon-tip cannulas (Tulip Medical Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) and Donofrio 16-gauge (Byron Medical Inc, Tucson, AZ, USA) straight blunt cannula. Transfer is begun by infiltrating the entry sites with a small wheel of 1% Xylocaine with 1:100,000 units of epinephrine and performing nerve blocks of the supraorbital, infraorbital, and mental nerve foramen. Generally, fat is placed from entry points perpendicular to the desired area of placement. Transfer is begun in the inferior orbital rim area. An 18-gauge needle is used to make an entry site at the level of the nasal ala just lateral to the nasolabial crease. The orbital rim is approached from below, the nondominant hand is used to place a finger just inside the orbital rim, and the 1.2-mm cannula tip is bounced off the finger while dispensing small quantities of fat with multiple small passes in a plane immediately above the periosteum (Fig. 15).

The medial orbital rim is treated, followed by the lateral rim. A second, more lateral entry site is often used to continue approaching the lateral rim from a perpendicular direction. In each location, medial and lateral, 1 mL of fat is placed. A third mL is then dispensed along the entire inferior orbital rim to even out and augment the area. Less fat is rarely used in this location and more may be added if needed. Often the 0.9-mm cannula is used to add fat into a slightly more superficial location to further augment the area. Quantities as large as 6 mL per side have been placed in this area, but more experience and care is indicated with these larger quantities because the risk of contour irregularities increases substantially. The lateral canthal area is treated with an entry site in the crows feet rhytids (Fig. 16). The 1.2- mm cannula is again used to infiltrate 1 to 2 mL of fat, blending it in with the inferior orbital rim fat. The superior orbital rim is then addressed by 1 or 2 entry sites in the forehead. The nondominant hand index finger is placed just inside the rim and the cannula is bounced off the finger while slowly placing fat in the plane just above the periosteum if no brow-lift has been performed and in the deep subcutaneous space if the subperiosteal plane has been violated (Fig. 17). Usually, 2 mL is placed along the superior orbital rim. Fat may also be infiltrated in a superficial subcutaneous plane in the forehead and glabella, but this is an advanced technique and should be used after gaining experience. The temporal area is blended in with the other periorbital areas with 1 to 2 mL of fat and the 1.2-mm cannula. The 16-gauge Coleman-Donofrio cannula is used to complete the transfer. This cannula is less fragile, and the remainder of the injections can be performed with greater ease and at a faster pace. The anterior cheek is addressed next by placing the nondominant index finger along the

lateral aspect of the nasolabial fold. The cannula is inserted via the crows feet entry site and 2 to 3 mL of fat is placed throughout the anterior cheek in superficial, mid, and deep cutaneous planes overlying the hollow of the malar septum. The lateral cheek is addressed by using the medial cheek entry site. The lateral extent of the anterior cheek augmentation is easily visualized. The lateral cheek is slowly built out from this point, injecting in multiple planes and tapering the malar eminence to a point over the zygomatic arch. This should create a teardrop appearance with the tapering superior aspect of the tear superiorlateral and a shadow under the lateral cheek that parallels the jaw line (Fig. 18). Usually, 2 to 3 mL is injected in this area. Larger volumes may be used for all these sites; the volumes given are conservative and generate substantial results with minimal risk. Further fat augmentation is performed in the buccal, perioral, and mandibular area but is beyond the scope of this article.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Postoperatively, the patient is asked to sleep with head upright and generously apply ice over the entire face. No wound care is necessary other than a small dab of ointment over the insertion sites. Patients experience a variable amount of bruising but a consistent amount of swelling. Patients are told to expect significant disfiguring swelling in the first week that decreases substantially by the end of the second week. Return to social activities can usually be achieved by the end of the second week in some patients and the third week in all. Some swelling and fat loss will occur through the sixth week and a small amount of volume will even be lost between 6 and 12 weeks. The volume stabilizes beyond this period, and long-term results can be expected with continued improvement in skin tone and texture even beyond 12 months, perhaps due to a growth factor effect that is an area of on-going research. Autologous fat contains the highest proportion of growth factors in the body.15 Some authors recommend freezing unused fat and reinjecting after 6 months. The authors have not found this necessary and rarely perform touch-up procedures. If a touch-up procedure is needed, fresh fat is harvested (Fig. 19A, B; Fig. 20A, B).

Fig. 19. Frontal and oblique views of 65-year-old woman 2 years after full-face fat transfer, full-face chemical peel, and lower facelift (A, B).

COMPLICATIONS OF FAT GRAFTING

Perhaps one of the major reasons many surgeons have been reluctant to adopt facial fat grafting as a surgical treatment option is the perceived transience of the result. Many surgeons have tried and given up on facial fat grafting because of failed attempts to achieve any durability. The authors believe that the reason for this failure, or perceived failure, stems from 2 problems: placing fat into facial areas that are not ideally treated with fat grafting, perioral area and lips, and poor operative technique.16 Most complications in fat grafting can be avoided by following the technique described, especially approaching the periorbital areas from perpendicular access points. Many types of potential complications can arise after fat transfer,

including reported incidences of infection, nerve injury, and arterial embolism. Although extremely rare cases of embolism and nerve injury have been reported, the authors believe that the chance of these occurring is further minimized when using blunt injection cannulas.17 Although still rare, the more likely types of fat transfer complications are contour problems, particularly in the periorbital region.

Fig. 20. Frontal and oblique views of 38-year-old woman 2 years after full-face fat transfer (A, B).

Complications can be divided into the following entities: lumps, bulges, persistent malar mound edema, overcorrection, and undercorrection. A lump is defined as a small, discrete mass of injected fat that may occur as a result of too large a bolus or too superficial a location. Dilute steroid injection is a reasonable first step in treating these areas, but persistence may require direct surgical excision. Abulge has a wider, cigar-rollappearance caused by imprecise placement of fat, overcorrection, or weight gain. Bulges caused by the first two may be treated by dilute steroid injection, direct excision, or microliposuction; the third is best managed with weight loss. Persistent swelling in the malar region should be distinguished from a bulge or overcorrection. The malar mound is a triangular-shaped elevation, anatomically delineated by the orbital septal-periosteal adhesion superiorly and the malar septum inferiorly. Themost important step in avoiding this complication is to identify the presence of a malar mound preoperatively and determine whether the patient has a history of cyclical swelling. If present post-operatively, time may resolve the condition, but if it persists, dilute steroid injections at 4- to 6-week intervals may be useful. Overcorrection is best avoided through a conservative fat transfer, especially when beginning. If a patient feels they are overcorrected, a period of at least 6 months should be allowed, following which, if the conditions still persists, microliposuction of the area may be required. Undercorrection is the easiest problem to correct and should be anticipated in every patient. All patients are counseled on the likelihood that a second fat transfer procedure may be needed to obtain the ideal result, although this rarely happens.

SUMMARY

Volume loss is an important component of facial aging, especially in the periocular region. Careful analysis of each patient aids the surgeon in selecting and discussing appropriate volume augmentation procedures. Syringe-based fillers or autologous fat can be used with excellent results in well-suited patients with minimal complications.

REFERENCES

- Ciuci PM, Obagi S. Rejuvenation of the periorbital complex with autologous fat transfer: current therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;66(8):168693.

- Gunter JP, Antrobus SD. Aesthetic analysis of the eyebrows. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;99(7): 180816.

- Matarasso SL, Carruthers JD, Jewell ML. Consensus recommendations for soft-tissue augmentation with nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (Restylane). Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 117(Suppl 3):3S34S.

- Andre P. New trends in face rejuvenation by hyaluronic acid injections. J Cosmet Dermatol 2008;7(4): 2518.

- Glavas IP. Filling agents. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 2005;18(2):24957.

- Fedok FG. Advances in minimally invasive facial rejuvenation. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;16(4):35968.

- Lowe NJ, Grover R. Injectable Hyaluronic acid implant for malar and mental enhancement. Dermatol Surg 2006;32(7):8815.

- Verpaele A, Strand A. Restylane SubQ, a non-animal stabilized Hyaluronic acid gel for soft tissue augmentation of the mid- and lower face. Aesthet Surg J 2006;26(1S):S107.

- Ridenour B, Kontis TC. Injectable calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres (Radiesse). Facial Plast Surg 2009;25(2):1005.

- Hevia OA. Retrospective review of calcium hydroxylapatite for correction of volume loss in the infraorbital region. Dermatol Surg 2009;35(10):148794.

- Donofrio LM. Techniques in fat grafting. Aesthet Surg J 2008;28(6):6814.

- Coleman SR. Facial augmentation with structural fat grafting. Clin Plast Surg 2006;33(4):56777.

- 13. Obagi S. Specific techniques for fat transfer. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2008;16(4):4017, v.

- Lam SM, Glasgold MJ, Glasgold RA. Complementary fat grafting. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer, Lippincott Willaims and Wilkins; 2007.

- ColemanSR.Structural fatgrafting:more than apermanent filler. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;118(Suppl 3). 108S120S.

- Coleman SR. Structural fat grafting. St. Louis (MO): Quality Medical Publishing, Inc; 2004.

- Glasgold RA, Glasgold MJ, Lam SM. Complications following fat transfer. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2009;21(1):538, vi.