INTRODUCTION TO FACIAL REJUVENATION

Changes in facial volume usually present beginning in a patient’s third decade and continue for the ensuing years. The extent and rapidity of facial aging vary between individuals and are strongly dependent on patient bony facial structure, soft tissue adipose content, and skin quality. Studies have analyzed the varying contributions of bone loss versus soft tissue loss in creating this aged appearance with interesting findings.

Restoration of lost volume may be performed by using syringe-based filling agents, such as hyaluronic acid, calcium hydroxyapatite, PLLA, and polymethyl methacrylate; a patient’s own adipocytes through autologous fat transfer; or surgically placed synthetic implants.

Each of these methods may lead to acceptable or even exceptional results in the appropriate hands. This article compares 2 of these techniques: autologous fat transfer and injection of PLLA.

FACIAL VOLUME LOSS: YOUTH VERSUS AGE

Periorbital

The youthful upper periorbital complex consists of a brow that is full over its entire height, propped up by the volume of the brow fat pad. Entire articles have been written and rewritten about the normal aesthetic height of the brow.

Often, however, brow shape and configuration are more important than brow height and perhaps lifting is not the solution to the aging brow in all cases. Comparing photos in the latest fashion magazine shows many examples of models, all of whom are exquisitely attractive, with significantly differing relationships between the brow and superior orbital rim (Fig. 1).

The upper eyelid also shows a variable fullness between patients; all may be considered youthful and attractive. Some youthful individuals have significant tarsal show with a deep superior orbital sulcus, a high lid crease, and little dermatochalasia.

Others have little tarsal show with a more prominent orbital fat component and, therefore, a much fuller-appearing upper eyelid. In the author’s opinion, the restoration of the youthful upper eyelid and brow complex must be tailored to a patient’s unique characteristics and must strive toward the restoration of youthfulness and not an ideal appearance based on the biases of a surgeon. Additionally, the forehead, temporal fossa, and glabellar area should all be convex and full and free of rhytids in the youthful face.

Infraorbital

The youthful lower eyelid complex consists of a short lower eyelid or, rather, a superiorly placed and full upper cheek. The lower eyelid cheek interface should be at the lower tarsal border and flow into a full convex upper anterior cheek.

This natural convex fullness results from the quantity of the lower eyelid suborbicularis oculi fat, superficial fat, and inferior orbital rim projection (Fig. 2). The infraorbital area ages prematurely when a negative vector configuration of the midface is present, much as the jaw line and neck age earlier in people with microgenia and a short thyromental distance (Fig. 3).

The youthful lower eyelid must also lack pseudoherniation of orbital fat. The cheek skin should be smooth over the underlying fat and the malar cheek fat pad should be shaped as a teardrop, with the rounded leading edge of the tear inferior-medial and tapering laterally over the anterior aspect of the zygomatic arch. The inferior aspect of this teardrop should create a subtle shadow in its interface with the buccal region that parallels that of the jaw line (Fig. 4).

Perioral

Inferior to the cheek fullness, the perioral region should be generally full with a soft transition from the anterior cheek fullness across the melolabial fold and into the cutaneous upper lip; however, presence of a melolabial fold is not necessarily a sign of aging and may be prominent in youth, especially when associated with a full round face.

Both the white cutaneous and red mucosal lips are full with associated natural peaks and valleys. The corners of the mouth are neutral or slightly up-turned and there is no marionette line formation.

Jaw and Neck

The jawline should be full and has more vertical height in youth without interruption from jowl formation. The angle of the jaw should have good lateral projection with a well-defined angle that approximates 90 as it ascends to the ramus.

Multifactorial Process of Aging

Aging is the culmination of a multifactorial process that includes the actions of gravity, volume loss, and skin changes due to intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

Periorbital aging

Volume loss in the upper periorbital area leads to exposure of harsh bony contours and the creation of shadows and concavities associated with aging. In the superior rim, this also leads to an apparent descent of the brow. As volume is lost over the bony orbital rim, the support for the soft tissue brow is lost. This effectively raises the position of the bony rim, which is now harsh and skeletonized, and leads visually to a drop in brow height. Illusions of the ratio of the pretarsal skin to lash line and brow also disrupt the normal ratios and offer an appearance of age. Lastly, volume loss in the temporal fossa and forehead contribute, and restoring this area to a youthful convex configuration assists in upper facial rejuventation.

Lower periorbital/cheek aging

Lower periorbital/cheek aging is perhaps most significantly influenced by volume-related changes and responds well to volume replacement. With time, the heart-shaped youthful face gives way to the more rectangular face of age as the loss of fullness in the lower eyelid and cheek region is combined with the increased width of the jawline at the jowl. Additionally, cheek volume loss creates the appearance of shadows as depleted superficial tissues fall and become tethered by various retaining ligaments. Shadows and contour disruptions arise in the lower eyelid and cheek between the orbital fat and the orbital bone. The lower eyelid gains apparent length in this process. Below this, the malar mound and malar septum create a second double contour in the cheek region (Fig. 5). Restoration of youth combines removal of orbital fat pseudoherniation, if present, and placement of volume into the orbital groove/tear trough and cheek region to restore the single convexity of the cheek and raise the cheek eyelid junction, thereby shortening the apparent lower lid height.7

Perioral aging

Perioral aging results in deepened nasolabial folds and loss of fullness of the white cutaneous and red mucosal lip, with resultant radial lip lines as well as marionette line formation. Loss of premaxillary volume, through bony changes primarily, causes the nose to become ptotic and the nasolabial angle to deepen.

Jawline aging

Age-related volume loss also occurs along the lower third of the face with recession of the jawline.8 Comparison of youthful and aged photos of patients often shows the significant mandibular vertical loss and the appearance of jowling may be as much a result of this change as descent of the jowl fat. Restoration of the jawline is usually accomplished with a combination of surgical lifting and the prejowl, chin, and mandibular angle as indicated.

PATIENT CONSULTATION

A consultation begins by listening. Patients are asked to express their age-related concerns. In the past, patients rarely mentioned that their face had become hollow or that they had a tear trough deformity. More recently, however, patients have become savvier about the contribution of volume loss and often present inquiring directly about its replacement.

Brow Assessment

Assessment begins with analysis of hair-bearing brow height in relation to the orbital rim. More often, the brow is at a reasonable height and the primary factor is loss of the brow fat pad volume and associated volume loss of the temporal fossa, forehead, and glabella.

It is only in 10% to 15% of patients that surgical brow lifting seems indicated, in the author’s practice. If available, a comparison of patients’ youthful photographs assists in the discussion of volume loss and brow position. Often, the indication for brow lift is more related to lateral brow ptosis, creating a flat brow configuration and associated melancholy appearance.

Lower Eyelid and Cheek Assessment

Assessment shifts inferiorly to the lower eyelid and cheek region. First, the presence of lower eyelid steatoblepharon must be determined. An assessment is made on lateral view whether or not any pseudoherniation projects anterior to an ideal convex line to be created at the lower eyelid cheek junction (Fig. 6). This is a judgment that improves with practice, but, especially for less experienced surgeons, if the decision is questionable, fat removal is recommended. If orbital fat reduction is indicated, it is performed conservatively, taking care to minimize the inferior extent of the submuscular dissection to allow an undisturbed tissue plane for placement of autologous fat both in the preperiosteal and submuscular/intramuscular planes. Anterior and lateral cheek volume loss is nearly always present to some degree.

If present, festooning should always be discussed. This is a difficult deformity to correct. In its early stages, filling around the malar mound provides improvement, but if a true edematous festoon is present, the fluctuations in swelling may be exacerbated by filling and may take weeks or months to resolve post-treatment, especially with fat transfer. Treatment of this condition is surgical and beyond the scope of this discussion.

Perioral Assessment

Perioral volume loss should be noted, but neither PLLA nor autologous fat is an ideal volume replacement choice for this area. Although the author always places fat in the perioral region with full face fat transfer, and fat may be placed essentially anywhere in the face safely, patients are warned that fat grafting rarely persists long term in the perioral region. It is postulated, much like skin grafting, that the constant movement of the perioral musculature and the lack of a stable bony platform to place the fat lead to shearing of the vascular ingrowth and eventual graft failure. PLLA has limitations in the perioral area as well.

Although it is safe to place PLLA in the cutaneous portions of the perioral unit, placement in the mucosal lip or too near the modiolus is ill advised because of development of palpable nodules.

Jowl Assessment

Assessment of the lower face related to volume involves assessing for the presence of a prejowl deficiency, microgenia, and/or mandibular angle deficiency. As discussed previously, the jowl descent is improved with lifting procedures.

PLLA TECHNIQUE

Preparation/Processing of PLLA

- PLLA is reconstituted with 6 mL of sterile bacteriostatic water and 2 mL of 1% Xylocaine, with 1:100,000 units of epinephrine at least 24 hours before injection—48 to 72 hours is preferable.

- The product is warmed with a heating pad on low setting beginning 1 hour before the planned injection.

- The reconstituted PLLA is then gently agitated and 2 mL drawn into the appropriate number of syringes.

Patient Preparation and Anesthesia

- No marking is performed on patients because the author prefers to see the shadows and hollows without disruption.

- Infraorbital nerve blocks are performed transorally.

- The PLLA is gently agitated by an assistant immediately before injection to ensure uniform suspension of the particles.

PLLA Injection for Full Face Restoration

- For full face restoration, the initial injection enters over the anesthetized anterior cheek, and the area of the inferior orbital rim is injected, taking care to aspirate before injection. The injection is deep, just over the periosteum. Injections in the central face, over the bony prominences, and temporal fossa injections are deep preperiosteal.

- Lateral face injections over the masseter and parotid or buccal areas are deep subcutaneous.

- PLLA should not be injected in areas of thin skin, such as the lower eyelid or lips, because palplable nodules may be evident in these areas.

- If the product cannot be adequately delivered superiorly into the orbital hollow, more superior filling is performed at a later date with a hyaluronic acid product.

- Injection then progresses from the anterior cheek to the lateral cheek, building the convexity to full correction and eliminating the concave malar groove. Because the injection contains Xylocaine, subsequent needle punctures should be performed, when possible, from treated areas.

- The premaxillary area is then filled as a deep injection and the buccal area in a subcutaneous fashion blending with the malar cheek.

- Injection then progresses to the temporal fossa. Again, this injection is deep and preperiosteal, when possible, but deep to the deep temporal fascia otherwise. Injection in this area is in boluses, taking care to aspirate preinjection. Again, full correction is the desired endpoint.

- The lateral brow is also filled at this time.

- If desired, the medial brow and glabellar area can be filled, but due to the deep locations of the supraorbital and supratrochlear neurovascular bundles, the injection in this area is subcutaneous.

- The lower third of the face is addressed with preperiosteal injection in the prejowl sulcus and as a bolus, avoiding the facial artery and mental foramen.

- The lateral mandibular area may then be filled in a deep subcutaneous plane over the parotid fascia.

- The marionette area is a subcutaneous injection and, if indicated, the anterior mandible is again a deep injection.

Note in frontal view the soft appearance of face and smooth transitions with improvement in the submalar area. Note especially in oblique view the distal cheek contour improvements.

Massage After Injections

- After injection, the face should be aggressively massaged to disperse the particles evenly.

- Massage is usually performed as each area is injected and again over the entire face once the procedure is complete.

Potential Sequelae of Injections

- Because the injection contains Xylocaine with epinephrine, mottled blanching is normal, as is transient motor nerve dysfunction.

- If eye closure is affected, reassure the patient and instruct in manual eye closure until this effect of local anesthetic resolves.

Timing for Multiple PLLA Injection Sessions

- PLLA is injected in 2 to 3 or more sessions, spaced at least 4 weeks apart. As the final endpoint is approached, longer intervals are recommended.

- Although full correction at each session is the endpoint, this is only temporary hydration. Patients need to be counseled that the effect regresses in 1 to 2 days. The PLLA particles then stimulate collagen production, creating lasting volume.

- Incremental correction is achieved with each injection, and variation of response occurs between patients. In some patients, a planned third session is canceled as result of an adequate result from the second session. Other patients might require a smaller fourth session to complete the correction.

- As the endpoint is approached, it is appropriate to delay further injections up to 3 months to avoid overcorrection and allow completion of the stimulatory process.

The published longevity of PLLA is 23 months, but the results likely persist beyond this time. (Fig. 7).

AUTOLOGOUS FAT TECHNIQUE

Anesthesia

- Autologous fat transfer is usually performed in an operating room under intravenous sedation supplemented with local anesthesia. Small secondary procedures may be performed under local anesthesia only.

- Skin resurfacing and lower eyelid blepharoplasty are performed before fat transfer, if indicated.

Donor Area Preparation

- Donor areas are marked out in the preoperative holding area with the patient standing. The abdominal area is the first choice of donor area, if available, followed by the medial and lateral thigh.9–12

- In the operating room and under sedation, the donor areas are infiltrated with 1% Xylocaine with 1:100,000 units of epinephrine mixed 1:1 with injectable 0.9% saline.

- The injection is performed with a 20-mL syringe and a 3-in x 25-gauge spinal needle. For the abdominal area, approximately 30 mL to 40 mL of solution is injected. Injection is placed in the immediate subcutaneous space and the prefascia space.

Note: No injection is placed in the midcutaneous plane where the fat is to be harvested, to minimize possible toxicity to adipocytes from the Xylocaine.

- Usually a minimum of 100 mL is harvested for full face transfer and up to 140 mL if the fat is of poor quality.

Fat Harvesting and Preparation

- Harvesting is performed with a small 15-blade entry point placed appropriately for the donor site.

- A bullet-tip 3-mm x 15-cm “Tenard type” cannula (Tulip Medical Products) is used for harvesting with a 10-mL syringe.

- Gentle (2–3 cm) aspiration pressure is used to prevent lipolysis.

- The harvested fat is then transferred into the PureGraft System (Cytori Therapeutics) (Fig. 8).

- The fat is rinsed and drained twice within the system with equal quantities of lactated Ringer solution.

- The fat is allowed to drain for a minimum of 3 minutes.

- Concentrated fat is then transferred to 1-mL injection syringes.

- Three different injection cannulas are used:

- 1.2-mm x 6-cm Spoon-tip cannulas (Tulip Medical Products)

- 0.9-mm x 4-cm Spoon-tip cannulas (Tulip Medical Products)

- Donofrio 16-gauge (Byron Medical) straight blunt cannula (Fig. 9)

Fat Transfer

See the video of fat transfer procedure accompanying this article at: https://www.facialplastic.theclinics.com/.

- Transfer is begun by infiltrating the entry sites with a small wheel of 1% Xylocaine with 1:100,000 units of epinephrine and by performing nerve blocks of the supraorbital, infraorbital, and mental nerve foramen.

- In general, fat is placed from entry points perpendicular to the desired area of placement.

- Transfer is begun in the inferior orbital rim area.

- An 18-gauge needle is used to make an entry site at the level of the nasal ala lateral to the nasolabial crease.

- The orbital rim is approached from below; the nondominant hand is used to place a finger just inside the orbital rim and the 1.2-mm cannula tip is bounced off the finger while dispensing small quantities of fat with multiple small passes in a plane immediately above the periosteum (Fig. 10).

- The medial orbital rim is treated first, followed by the lateral rim. 1 mL of fat is placed in each location, medial and lateral. A third 1 mL of fat is then dispensed along the entire inferior orbital rim. Less quantity is rarely used in this location and more may be added if needed. Often, the 0.9-mm cannula is used to add fat into a slightly more superficial location to further augment the area.

Note: Quantities as large as 6 mL per side have been placed in this area, but more experience and care are indicated with these larger quantities because the risk of contour irregularities increases substantially.

The lateral canthal area is next treated with an entry site in the crow’s feet rhytids (Fig. 11). The 1.2-mm cannula is again used to infiltrate 1 mL to 2 mL of fat, blending it in with the inferior orbital rim fat.

The superior orbital rim is then addressed by 1 or 2 entry sites in the forehead, again placing the nondominant hand index finger just inside the rim and bouncing the cannula off the finger while slowly placing fat.

Note: Fat is placed in the plane just above the periosteum if no brow lift has been performed. It is placed in the deep subcutaneous space if the subperiosteal plane has been violated (Fig. 12).

- Usually, 2 mL is placed along the superior orbital rim.

- Fat is also infiltrated in a superficial subcutaneous plane in the forehead and glabella and, if indicated, into the upper eyelid sulcus. Note: The preceding is an advanced technique and should be introduced only after sufficient experience has been gained.

- The temporal area is then blended in with the other periorbital areas with 1 mL to 3 mL of fat deep to the deep temporal fascia with the 1.2-mm cannula.

- The 16-gauge Donofrio cannula is then used to complete the transfer except in the mucosal lip where the 0.9-mm cannula is again used.

Note: The Donofrio cannula is less fragile than the spoon-tip cannulas, so the remainder of the injections can be performed with more ease and at a faster pace.

- The anterior cheek is addressed next by placing the nondominant index finger along the lateral aspect of the nasolabial fold mound.

- The cannula is then inserted via the crow’s feet entry site and 2 mL to 3 mL of fat is placed throughout the anterior cheek in superficial, mid, and deep cutaneous planes overlying the hollow of the malar groove.

- The lateral cheek is then addressed by utilizing the medial cheek entry site.

Note: The lateral extent of the anterior cheek augmentation is easily visualized. The lateral cheek is slowly built out from this point, injecting in multiple planes and tapering the malar eminence to a point over the zygomatic arch. This should create a teardrop appearance with the tapering superior aspect of the tear superior-lateral and a shadow under the lateral cheek, which parallels the jawline (Fig. 13).

Note: Usually 2mLto 3mLis injected in the lateral cheek area. Larger volumes may be used for all these sites; the volumes given are conservative and generate substantial results with minimal risk.

- 1–2 mL is then placed deep over the precanine fossa and base of the pyriform aperature.

- 1–2 mL is placed subcutaneous in the nasolabial fold.

- 1 mL is placed in the cutaneous lip.

- 2 mL is placed preperiosteal in the prejowl sulcus.

- 2 mL is placed subcutaneous for the marionette line.

- 0.5 mL to 1 mL is then placed in each mucosal lip, taking care not to obliterate the midline depression of the lower lip.

Note: All volumes quoted are unilateral.

POSTOPERATIVE PATIENT CARE

Postoperatively, patients are asked to sleep with the head upright and apply ice generously over the entire face. No wound care is necessary other than a small dab of ointment over the insertion sites.

Fig. 14. 65-year-old woman, frontal (A) and oblique views (B), 2 years after full face fat transfer, full face chemical peel, Upper blepharolplasty and lower facelift.

Fig. 15. 38-year-old woman, frontal (A) and oblique (B) views, 2-years after full face fat transfer.

Patients experience a variable amount of bruising but a consistent amount of swelling. Patients are told to expect significant disfiguring swelling the first week, which decreases substantially by the end of the second week. Return to social activities can be achieved by the end of the second week in most patients and the third week in all.

Some volume reduction occurs through the sixth week and a small amount of volume may be lost between 6 and 12 weeks. The volume stabilizes beyond this time period and long-term results can be expected except in the perioral region (Figs. 14 and 15).13–15

CHOOSING PLLA VERSUS FAT

In the author’s practice,PLLAand fat are the primary choices for full face volume restoration. Although both procedures may be used for regional placement, the author finds that patients with isolated regional deficiencies often desire immediate corrections and choose products other than PLLA or fat.

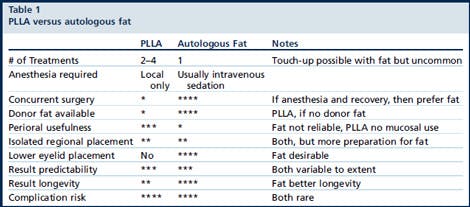

Autologous fat has the benefit of requiring only 1 procedure, but it requires an anesthetic and 2 to 3 weeks of social recovery. PLLA requires several treatment sessions but is usually performed under local anesthesia only.

Usually PLLA has little to no postoperative bruising or swelling and while it can be used in conjunction with a surgical procedure; most patients choose autologous fat when having concurrent surgical procedures because they are recovering from other procedures, they do not need several treatment sessions, and autologous fat affords greater longevity.

Usually if patients are interested in isolated volume augmentation without other surgical procedures, PLLA is used; however, certain patients desire the potential for greater longevity and the soft nature of fat and choose to have fat grafting as an isolated procedure.

PLLA is not advised in the thin lower eyelid skin, but a hyaluronic acid product can be combined with PLLA to accomplish that goal. Autologous fat provides natural results for the thin lower eyelid skin and can also be used in the upper orbital sulcus, whereas PLLA is not advised.

The surgeon’s role is to explain the indications, risks, benefits, and alternatives of the available procedures and let patients choose, with appropriate guidance. Table 1 summarizes the comparison of procedures.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Autologous fat transfer has been criticized by some surgeons for having a lack of longevity, lack of predictability, and potential for irregularities, especially in the lower eyelid region.

Although the author agrees that fat transfer is predictably unreliable for treatment of the perioral area, he has had success and reliability elsewhere in the face and has had patients with consistent volume retention more than 5 years after the procedure.

Patients do need to be counseled preoperatively regarding the varying survival of autologous fat but the author finds that even patients with less than average survival of transferred fat are satisfied with their results and that few secondary procedures are performed.

Autologous fat offers replacement of like tissue and is soft and natural in its appearance. PLLA, when used to gain the same degree of correction, can at times feel somewhat firm and stiff.

Autologous fat techniques vary between surgeons without clear superiority in many cases.16 The author implemented use of the PureGraft System approximately 28 months and believes that it has added consistency to outcomes.

With the previous use of centrifugation, some poorer quality harvested fat was difficult to predict. A recent presentation by Glasgold (American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2012 fall meeting) seems to support this, but more evidence needs to be gathered.

Many exciting advances in autologous fat transfer and stem cell therapy are under investigation and promise increasingly reliable results in the future.17

SUMMARY

Facial volume loss both from bone loss and soft tissue loss contributes significantly to facial aging. Understanding the changes that occur and striving to restore patients to their youthful state, rather than removing and lifting tissue in isolation, are paramount.

Fortunately, many treatment options have been introduced in the past decade to restore lost volume, and great advances in understanding of youthful contours, both on the surface and in the facial fat pads, has occurred and continues to advance.

Both PLLA and autologous fat transfer offer improvement in the treatment of facial volume loss. Using each procedure appropriately to bring the greatest degree of satisfaction to patients remains the goal.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fsc. 2013.02.007.

REFERENCES

- Ciuci PM, Obagi S. Rejuvenation of the periorbital complex with autologous fat transfer: current therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;66(8):1686–93.

- Shaw RB, Katzel EB, Koltz PF, et al. Aging of the mandible and its aesthetic implicatioins. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;125(1):332–42.

- Shaw RB, Kahn DM. Aging of the Midface bony elements: a three-dimensional computed tomogragphic study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119(2):675–81.

- Donofrio LM. Fat distribution: a morphologic study of the aging face. Dermatol Surg 2000;26(12):1107–12.

- Rohrick RJ, Pessa JE, Ristow B. The youthful cheek and the deep medial fat compartment. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;121(6):2107–12.

- Gunter JP, Antrobus SD. Aesthetic analysis of the eyebrows. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;99(7):1808–16.

- Lambros V. Observations on periorbital and midface aging. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;120(5):1367–76.

- Lambros V. Models of facial aging and implications for treatment. Clin Plast Surg 2008;35(3):319–27.

- Donofrio LM. Techniques in fat grafting. Aesthet Surg J 2008;28(6):681–7.

- Coleman SR. Facial augmentation with structural fat grafting. Clin Plast Surg 2006;33(4):567–77.

- Obagi S. Specific techniques for fat transfer. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2008;16(4):401–7, v.

- Lam SM, Glasgold MJ, Glasgold RA. Complementary fat grafting. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer, Lippincott Willaims and Wilkins; 2007.

- Coleman SR. Structural fat grafting: more than a permanent filler. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 118(Suppl 3):108S–20S.

- Coleman SR. Structural fat grafting. St Louis (MO): Quality Medical Publishing, Inc; 2004.

- Glasgold RA, Glasgold MJ, Lam SM. Complications following fat transfer. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2009;21(1):53–8, vi.

- Phanette G, Brown SA, Oni G, et al. Fat grafting: evidence-based review on autologous fat harvesting, processing, reinjection, and storage. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012;130(1):249–58.

- Butala P, Hazen A, Szpalski C, et al. Endogenous stem cell therapy enhances fat graft survival. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012;130(2):293–306.